(1)

(1)

Tom Brandis

29 October 2023

Physicists believe that the universe is expanding. I will explore evidence for this. I will discuss different theories explaining this including theories containing dark energy such as a cosmological constant, the ΛCDM model and quintessence. I will then discuss alternative modified gravity theories. Finally I will come to a conclusion on whether dark energy is the best explanation for the expansion of the universe.

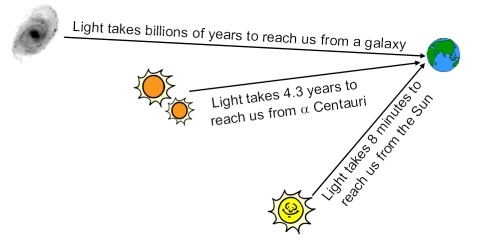

In 1929, Edwin Hubble measured the rate that different galaxies were moving away from us using redshift, a phenomenon where light is made more red when it is emitted from an object that is moving away from an observer. This is because the wavelength of light lengthens as the objects move apart.

Looking at galaxies different distances away allowed Hubble to look at galaxies in different points in time, as light from further away galaxies has travelled for longer.

This means light from further away left the object a longer time ago. When we look at far away objects we see them as they were in the past, the further away, the further back in time (Koren, 2022).

(1)

(1)

(Swinburne University of Technology, n.d.)

Hubble’s redshift measurements found that closer galaxies were moving away more quickly than further away galaxies (Hubble, 1929). This meant that galaxies are moving away more quickly now than in the past and that the rate the universe is expanding is increasing.

This was unexpected and raised new questions about the nature of the universe. Before Hubble’s measurement, it was assumed that the universe was mainly stable.

In 1931, Lemaître, proposed that the universe is expanding, logically it would get smaller back in time until it was as small as it is possible to be. He theorised that the universe started as a “single primordial atom” that expanded outwards to become the universe as we know it today. This idea has since become popular as the theory of the big bang.

Further measurements found that whilst the rate of expansion of the universe is now increasing it hasn’t always been. When the universe began it was expanding very fast but the rate of expansion was slowing down. Then around 4 billion years ago the expansion stopped slowing down and started speeding up.

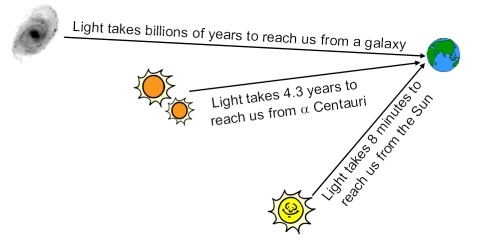

(2)

(2)

(BBC Bitesize, n.d.)

In this graph the rate of expansion is represented by the gradient of the line. It started very high before decreasing until about 4 billion years ago when it started to increase and is expected to do so exponentially.

One explanation for this is that the expansion of the universe is controlled by two opposing forces, one pulling in and another pushing out and that at the start of the universe the inward one was more powerful than it is now. The turning point around 4 billion years ago would have happened when the outward force became more powerful than the inward force.

In this model of the expansion of the universe, gravity caused by matter pulls inward and energy causes the outward push. In these models there is not enough energy that we know about in the universe to push outwards enough to explain the expansion of the universe. This is why the idea of dark energy is needed. This is energy that we cannot detect.

As well as being a useful tool, redshift is interesting in the way that it influences the energy of a light wave. The energy of a wave is:

(3)

(Oxford Cambridge and RSA [OCR], 2020)

E is energy, λ is the wavelength of the wave and both h and c are constants. This means that energy is inversely proportional to the wavelength:

(4)

When redshift causes the wavelength to increase, energy from the wave is lost in a way that seems to break the first law of thermodynamics that tells us that “if a system is isolated, its internal energy must remain constant.” (Ling, et al, 2023). The law can be represented as:

(5)

(Ling, et al, 2023)

Where Eint is the internal energy, Q is the heat added to the system and W is the work done by the system. There are several explanations for the apparent breaking of this rule.

One explanation would be that the universe is not an ‘isolated system’ and that energy is leaving the universe. An argument against this is that redshift has an opposite, rarer, effect called blueshift, where light wavelengths are shortened when an emitting object is moving towards an observer. In this situation, the light gains energy. If energy is permanently lost from the universe in redshift, this should not be possible.

An alternative explanation for the energy loss would be that the first law of thermodynamics is wrong, at least when space is changing shape. Rather than energy remaining constant, energy remains constant relative to the space it moves through. It can be argued that because an expanding universe doesn’t have “time-translation invariance”. This is the idea that nothing changes over time unless something causes it to. If the universe does not have this then things could change over time without cause, meaning the amount of energy in a light wave could change over time (Carroll, 2010).

Finally, energy lost from redshift could be stored somewhere. This would allow light to gain and lose energy without overall gain or loss of energy in the universe. The question then is where would the energy be stored?

Some scientists think that when redshift occurs, the light does work on the universe, and the opposite when blueshift occurs. When redshift occurs the size of the universe increases and the energy in the light decreases. This implies that energy is stored in some way in the size of the universe.

|

Phenomenon |

Energy in the light |

Size of universe (dark energy) |

|

Redshift |

Less |

More |

|

Blueshift |

More |

Less |

(6)

This energy stored in the universe is considered dark energy because it cannot be interacted with or detected.

When thinking about the expansion of the universe, some of the most important equations are the Friedemann equations. They describe general relativity, Einstein's theories and equations, for an isotropic and homogeneous universe. This means that assuming that the universe is the same everywhere, which if we use a big enough scale it is, we can see how it changes over time. (Siegel, 2021)

The first Friedemann equation describes how the rate of expansion of the universe is related to the mass and energy density:

(7)

(Friedemann, 1922)

Where:

H is the rate of expansion

G is the gravitational constant

c is the speed of light

p is the average density of matter and energy

S is the scale factor

k is the curvature of the universe

Out of these G, c and S are constant so we are most interested in H, p and k. This means that, ignoring all constants:

(8).

(Friedemann, 1922)

This means that as the expansion is increasing then either the curvature or the density of the universe is increasing, otherwise the equation would no longer be true. This is unexpected as, if the universe is expanding, then energy and matter would be spread out, meaning the density would decrease rather than increase.

This suggests that either more energy or mass is created as the universe expands. If more mass was created it would lead to more gravity, which could ultimately leading to the universe collapsing. Therefore there must be an increase in energy. This energy is dark energy.

Initially it seems like creation of more energy cannot be possible as energy cannot be created or destroyed according to the first law of thermodynamics (equation 5). There are multiple theories for why this can be possible.

One theory is that dark energy is an inherent property of space called the cosmological constant. This would mean that space itself has energy to it. This idea was first used by Einstein in order to balance against the gravitation attraction of matter in order to construct a model of a static universe. (Einstein 1917). This cosmological constant is usually called lambda (Λ). The theory involving the cosmological constant is called the ΛCDM model – CDM stands for cold dark matter, the other notable component in it. If the cosmological constant is out of balance with gravity it would create either a collapse or accelerating expansion, because as it expands more energy is brought into existence.

When Einstein first used the cosmological constant he assumed that it must be balanced with gravity, however after the discovery of the expansion if the universe, it was realised that if it was out of balance it could create a situation like that seen in our own universe.

The main problem with accepting this theory and other dark energy theories is that the energy doesn’t seem to come from anywhere, violating the first law of thermodynamics (equation 5).

However the theory can be combined with the theory that redshift does work on the universe (table 6). This could mean it doesn’t break the first law of thermodynamics. For this reason, the ΛCDM model is the most popular among scientists. It provides a complete explanation of the evolution of the universe by saying that there is both energy and matter that we can’t detect.

A similar theory is that of quintessence. This theorises a form of energy that is similar in effect to a cosmological constant but that is not necessarily spread out equally as a part of space but instead can flow around and have different densities. It is characterised by its equation of state:

(9).

In this equation, p is pressure and q is energy density. The closer w is to -1, meaning the lower the pressure and the higher the energy density, the greater the accelerating effect (Steinhardt, n.d.). This could allow for different rates of expansion in different places in space as suggested by Migkas et al., (2020).

As we saw in graph 2, there is another problem with the expansion of the universe, that it was very fast for a short period at the start. One theory explaining this is the existence of early dark energy.

This theory says that there was a different type of dark energy that made up around 10% of the energy in the early universe but then decays quickly. This would mean that there would be a high enough energy density in the early universe to cause the rapid acceleration at the start before decaying. This allows the expansion to decelerate before the non-early dark energy tips the balance back in favour of energy, causing it to accelerate again. (Falk, 2023) (Kamionkowski and Riess, 2023).

What else could be causing the expansion of the universe?

Modified gravity is an alternative theory based on not assuming that gravity works the same on every scale. Modified gravity theories change the equations so that they act differently on very small or very large scales.

Modified gravity theories can be written so that dark energy is not needed to explain how the universe works.

One type of modified gravity theory is f(R). This introduces a function to the Ricci scalar (R) a variable in Einstein’s field equations (Garbutt, n.d.) that describes how much the universe differs from a Euclidean space (Hirvonen, n.d.).

This is done through modifying the Hilbert-Einstein action. Actions in physics are abstract quantities that describe the overall motion of a system (Encyclopædia Britannica, n.d.). The Hilbert-Einstein action is usually defined as:

(10)

(Feynman, 1995, p. 136)

In the f(R) modified gravity theory this is written as:

(11)

(Capozziello and De Laurentis, 2015)

Here a function, f is applied to R, the Ricci scalar in the equation. The function f can be anything and several alterative have been proposed.

These theories are appealing as it is more testable and measurable than dark energy theories, that rely on something that is very hard to interact with.

Another similar modified gravity theory called f(Q) is interesting as it is more accurate at predicting the expansion of the universe than the dark energy based model. (Feldman, 2023)

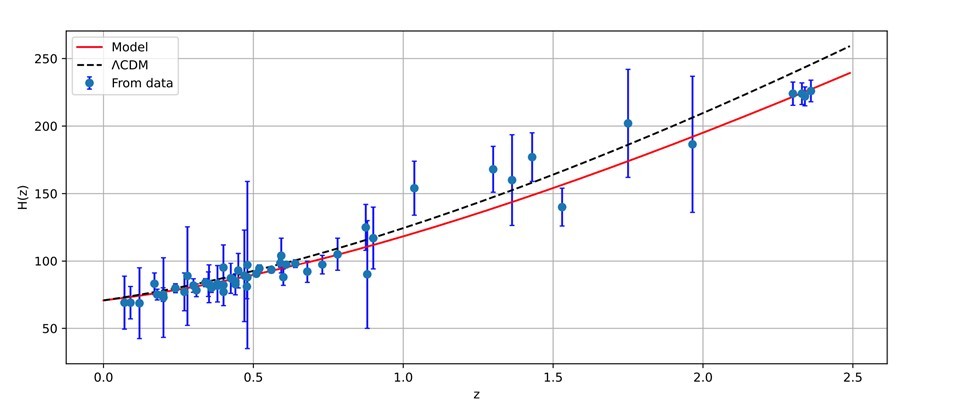

(12)

(12)

(Narawade and Mishra, 2023)

This graph shows that the f(Q) model (in red) more closely follows the data points than the ΛCDM model – with dark energy. This model is quite new, meaning it hasn’t been tested extensively yet, however it and similar models could be promising alternatives. (Anagnostopoulos, Basilakos and Saridakis, 2021).

Conclusion

In conclusion I think that dark energy, specifically the ΛCDM model, is the best explanation for the expansion of the universe because it seems most plausible and the evidence fits it well. It is the most popular theory among physicists who specialize in this area however this is still an emerging area of research and it seems likely that in the future there will be improvements to the model or a model that fits the evidence better.

Alternatives that do not feature dark energy, whilst interesting, are not as popular. Most other theories have not been developed to the extent of the dark energy theory.

Bibliography

Anagnostopoulos, F.K., Basilakos, S. and Saridakis, E.N. (2021) ‘First evidence that non-metricity f(Q) gravity could challenge ΛCDM’, Physics Letters B, 822, p. 4. Available at: https://doi.org/136634.

BBC Bitesize (no date) Expansion of the Universe [Digital]. Available at: https://bam.files.bbci.co.uk/bam/live/content/zd23kqt/large (Accessed: 18 October 2023).

Capozziello, S. and De Laurentis, M. (2015) ‘F(R) theories of gravitation’, Scholarpedia. Available at: http://www.scholarpedia.org/article/F(R)_theories_of_gravitation (Accessed: 20 October 2023).

Carroll, S. (2010) ‘Energy Is Not Conserved’, 2 February. Available at: https://www.preposterousuniverse.com/blog/2010/02/22/energy-is-not-conserved/ (Accessed: 17 October 2023).

Einstein, A. (1917) Cosmological Considerations of the General Theory of Relativity.

Encyclopædia Britannica (no date) ‘Action (Physics)’. Available at: https://www.britannica.com/science/action-physics (Accessed: 20 October 2023).

Falk, D. (2023) ‘The “least crazy” idea: Early dark energy could solve a cosmological conundrum’, Knowable Magazine, 28 September. Available at: https://knowablemagazine.org/article/physical-world/2023/early-dark-energy-resolving-cosmic-acceleration-mismatch (Accessed: 18 October 2023).

Feldman, A. (2023) ‘Modified theory of gravity eliminates the need for dark energy’, Advanced Science News, 19 April. Available at: https://www.advancedsciencenews.com/modified-theory-of-gravity-eliminates-the-need-for-dark-energy/ (Accessed: 18 October 2023).

Feynman, R. (1995) Feynman lectures on gravitation. Available at: https://archive.org/details/feynmanlectureso0000feyn_g4q1/page/n5/mode/2up (Accessed: 20 October 2023).

Friedemann, A. (1922) ‘Über die Krümmung des Raumes’, Zeitschrift für Physik, 10(1), pp. 377–386. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01332580.

Garbutt, J. (n.d.) ‘Overview of Modified Gravity’. Available at: https://www.imperial.ac.uk/media/imperial-college/research-centres-and-groups/theoretical-physics/msc/dissertations/2020/John-Garbutt-Dissertation.pdf (Accessed: 19 October 2023).

Hirvonen, V. (n.d.) ‘The Ricci Tensor: A Complete Guide With Examples’, Profound Physics. Available at: https://profoundphysics.com/the-ricci-tensor/ (Accessed: 20 October 2023).

Hubble, E. (1929) ‘A RELATION BETWEEN DISTANCE AND RADIAL VELOCITY AMONG EXTRA-GALACTIC NEBULAE’, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 15. Available at: http://homepages.warwick.ac.uk/~phsep/px311/picturescosmology/Hubble%27s%201929%20Paper.htm (Accessed: 16 October 2023).

Kamionkowski, M. and Riess, A.G. (2023) ‘The Hubble Tension and Early Dark Energy’, Annual Review of Nuclear and Particle Science, 73(1), pp. 153–180. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-nucl-111422-024107.

Koren, M. (2022) ‘The Webb Space Telescope Is a Time Machine’, The Atlantic, 22 July. Available at: https://www.theatlantic.com/science/archive/2022/07/james-webb-telescope-image-most-distant-galaxy/670616/ (Accessed: 19 October 2022).

Ling, S.J., Moebs, W. and Sanny, J. (2023) University Physics. Available at: https://openstax.org/books/university-physics-volume-2/pages/3-3-first-law-of-thermodynamics (Accessed: 17 October 2023).

Migkas, K. et al. (2020) ‘Probing cosmic isotropy with a new X-ray galaxy cluster sample through the LX–T scaling relation’, Astronomy and Astrophysics, 636(A&A Volume 636, April 2020), p. 42. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1051/0004-6361/201936602.

Narawade, S.A. and Mishra, B. (2023) ‘Phantom Cosmological Model with Observational Constraints in f(Q) Gravity’, Annalen der Physik, 535(5). Available at: https://doi.org/10.1002/andp.202200626.

Oxford Cambridge and RSA (2020) ‘Data, Formulae and Relationships Booklet’. Available at: https://www.ocr.org.uk/Images/363796-units-h156-and-h556-data-formulae-and-relationships-booklet.pdf (Accessed: 17 October 2023).

Siegel, E. (2021) ‘Surprise: the Big Bang isn’t the beginning of the universe anymore’, Big Think, 13 October. Available at: https://bigthink.com/starts-with-a-bang/big-bang-beginning-universe/ (Accessed: 19 October 2023).

Steinhardt, P.J. (n.d.) ‘A Quintessential Introduction to Dark Energy’. Princeton University. Available at: https://web.archive.org/web/20060718133138id_/http://www.physics.princeton.edu:80/~steinh/steinhardt.pdf (Accessed: 16 October 2023).

Swinburne University of Technology (no date) Lookback Time [Digital]. Available at: https://astronomy.swin.edu.au/cms/cpg15x/albums/userpics/lookback.jpg (Accessed: 18 October 2023).